The Bell Jar: Intermedial adaptation

In this essay, written while I was an undergraduate in the School of Arts and Education at Middlesex University, I reflect on the making process of The Bell Jar, an intermedial adaptation of Sylvia Plath’s novel which we staged at the University in January 2013; drawing together the experience of producing the show with wider critical theories and influences surrounding intermedial performance-making. My use of certain terminologies in the essay, such as “multi-disciplinary” and “mixed-media”, reflects a preliminary understanding of the practices which has evolved in sophistication since time of writing.

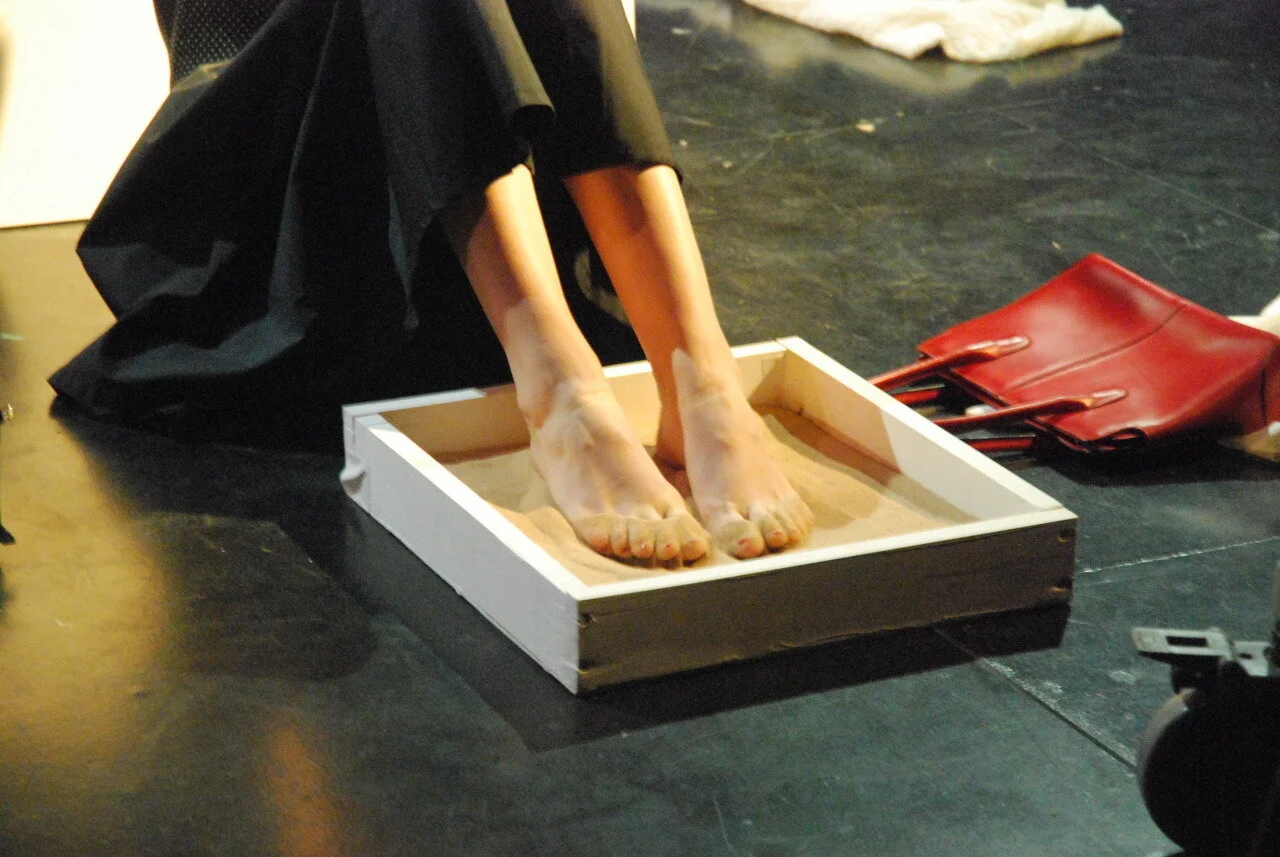

The Bell Jar (dir. Bruce Adams & William Bowden), 2013. Photograph: Will Bowden.

“While some critics have argued that the presence of the mediated images impairs the possibility of the actor creating the sort of shared relationship with an audience that is often seen as an essential characteristic of live theatre, it has been shown that this is not necessarily the case. Indeed, often it might be argued that the very conjunction of the mediated image with the live performer heightens the spectator’s sense of the liveness of the performer.”

Greg Giesekam (249)

Intermedial work, in various guises and to differing extents, has existed in theatre for almost a century. Projected backdrops began to appear in the early 20th century, while more experimental practitioners such as Erwin Piscator explored the more extensive integration of film into theatre as early as 1924. In Staging The Screen, Greg Giesekam identifies a continuum between multimedia at one end; wherein a non-theatrical medium might be used in a similar function to lighting or sound in order to establish a setting or “imply modern parallels with the action [of a Shakespeare text]”; and intermedia at the other, which implies a much more complex interaction between performer and technology, “where neither the live material nor the recorded material would make much sense without the other” (8).

6 Characters in Search of an Author (dir. William Bowden), 2012. Tika Mu’tamir as the Producer, between Nathan Bourne and Dan Henry, looks imposing on stage but vulnerable in the live video (behind). Photograph: Jess Mann.

Key to our work in creating The Bell Jar was a process which embraced a collaborative, multi-disciplined ensemble approach, working in a mixed-media format which utilised technology and filmic devices in an intermedial way. The work was conceived as an extension of the form we had begun to experiment with a year earlier in 6 Characters in Search of an Author. This production, a contemporary adaptation of Pirandello’s text set in a documentary film collective’s editing suite, utilised live feed camera work to highlight and contrast key moments, blurring the distinction between film and theatre (and realism and surrealism), and underlining that act of illusion.

In The Bell Jar we wanted to explore the same mixed-media approach but to a much greater extent, and integrated much deeper within the storytelling. Inspired by Katie Mitchell’s multimedia works at the National Theatre between 2006 and 2008, and the fragmented aesthetic used by ensemble companies such as Filter and Complicite, we wanted to create a work which would engage an audience using means beyond those of a traditional text-based play: the visual aesthetic should play as important a role in the storytelling as the verbal communication. Our first objective, then, was to select a source text which could act as a rich enough source for this kind of image-making.

Again drawing inspiration from Mitchell’s use of novels (Virginia Woolf’s The Waves and Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot); as well as earlier work in my undergraduate training when I directed The Street of Crocodiles, adapted by Complicite from Bruno Schulz’s short stories; we felt that a non-theatrical prose source would provide a generous, and adequately challenging, starting point. We considered a number of short stories by Franz Kafka, a verbatim text by Eric Bogosian titled Notes from Underground, contemporary novels Solar and On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan (the latter of which we ultimately staged the following year), and Sylvia Plath’s 1963 novel The Bell Jar. The latter caught our attention for a number of reasons: its clinical study of female depression was thematically interesting to us; its fragmented succession of memories and flashbacks would be challenging to stage but would embrace the fragmented aesthetic we wanted to explore; and Plath’s prose is rich with poetic images and metaphors which we felt could anchor the style of storytelling that we were developing.

In an interview with The Culture Show in 2008, Mitchell cites “the chaos of the construction”, wherein “construction” might imply anything from a visible costume change to the positioning of a camera by an actor, and its direct contrast with the finished stage images as central to the aesthetic of her work at the National between 2006 and 2008. Taking this description, and identifying similar deconstructive aesthetics in the work of other companies such as Filter and Complicite, we began to use the term “aesthetic of chaos” to describe the theatrical style that we were exploring in our work on this module. I discussed the potential theoretical definitions of the “aesthetic of chaos” at greater length in an earlier essay (later reproduced on this website), from which I will include the following excerpt:

“Through this undisguised interaction between performer and hardware, the visible presence of technology therefore plays an integral role in the aesthetic of a chaotic performance, acting as ‘a live participant, with almost equal status to an actor’. The exposed mechanics of the performance reveal the act of theatre as a machine, within which actors and apparatus are balanced components.” (Adams 8)

As well as building on our use of live feed camera work in 6 Characters In Search Of An Author, we also wanted to explore other methods of live construction via technology: notably, foley techniques. Foley is another filmic device that recreates sound effects which cannot be captured on-location, often using artefacts that bear no resemblance to the sound being mimicked. Early on in the process we decided to make prominent use of live sound; we were determined that all sound effects should be created and performed live, while the pre-recorded sound design would be restricted to providing texture and tone to support the performance. Similarly, while 6 Characters In Search Of An Author made use of pre-recorded output as well as live feed, we decided to focus solely on live camera output with all shots constructed and recorded in the presence of an audience. Therefore, the liveness of the technological aspects was a fundamentally important factor in the theatricality of the piece.

“Such work implicitly acknowledges the spectators’ role in completing the performance – something which applies to all theatre, of course, but which is often ignored.” (Giesekam 249)

Indeed, some of the most pleasurable reactions from the audience occurred at moments when their imaginative engagement was a required element in completing the scenography, “joining the dots” between various clues. One such example (in a direct nod to Mitchell’s practice at the National Theatre) was composed of four major elements:

Ester Mangas Fernandez in The Bell Jar. Photograph: Will Bowden.

The performer sat behind a table, while two other performers place a sheet of perspex in front of her and spray water onto the perspex.

A camera wheeled in by two more performers and focused closely on the first performer’s face behind the perspex.

The pre-recorded sound of rain.

A sixth performer, who represented the protagonist’s internal thoughts, speaking the following text (Plath 17):

The city hung in my window, flat as a poster, glittering and blinking, but it might just as well not have been there at all, for all the good it did me.

Waves (dir. Katie Mitchell), 2006. Photograph: Stephen Cummiskey.

The image is completed when the close-up shot appears projected onto a tactile white drape above the stage. The audience are implicitly invited to piece together these four “clues”, arriving at the completed illusion of the protagonist looking out of her hotel window on a rainy night.

A similar, much simpler, illusion could have been created had we opted to use pre-recorded video: this would have required only the first performer to act as the physical representation of the central character, Esther. However, by involving a further five live performers in the creation of the image (behaving in a way that, through their interaction with the technology they are operating, is incongruous with the characters and story), as well as exposing the spectators to the machinery used to compose this image (camera, tripod, dolly, cable feed, perspex, spray bottle), the audience becomes complicit in the liveness of the act of theatremaking.

“As soon as the audience cotton on to the fact that every element is live, [they realise that] there could be an error at any moment, and there’s a great joy in participating in that.” (Katie Mitchell in conversation with The Culture Show, 2008)

Dan Henry performing foley work in The Bell Jar. Photograph: Will Bowden.

This liveness could have been realised to a greater extent had we followed through more thoroughly on our intention to integrate live foley work. While indeed almost all of the sound effects in the performance were constructed live, using a prop table and a microphone positioned upstage left in full view of the audience (pictured below left), use of such sound effects was heavily concentrated in the first third of the production and became more neglected as the performance continued.

The final pre-recorded sound design included three ambient “background” effects: the sound of rain, the noise of a city, and the sound of waves washing up on a beach. To construct these atmospheric effects live would have required greater effort (and time commitment) than the effects created earlier in the play (drinks being poured, change being dropped in a tip-tray), but could have been possible had we approached the live sound with more foresight. This is worth considering in future productions of this style or, indeed, if this particular production is revisited.

However, weighting the live sound construction towards the beginning of the play played an important role in establishing the style of the piece, allowing the audience time to acclimatise to the conventions with which we were experimenting before introducing more complex moments such as the “window example” given above. (Indeed, the performance opened with an extended sequence in which each of the cast used a prop to add a layer to a soundscape; see below.) Had these moments occurred earlier, before the audience became used to the performance style, it is possible that they might have been confusing and unclear.

“There has been a strong move to make and view theatre as a plastic rather than an intellectual art form. The ability of theatre to generate a plethora of visual, aural and physical images all at once is a function of its new-found willingness to make action rather than language the medium in which performances are constructed.” (Mitter & Shevtsova xviii)

In the show’s opening sequence, Zakk Hein captures sound effects performed by the cast. Photograph: Will Bowden.

Despite initially borrowing heavily from Katie Mitchell, it was important that we used the devising process to develop an aesthetic and style that was unique to our company. In particular we were keen to retain the live interaction of bodies in space, which Mitchell largely dispenses with in her multimedia works – keeping individual actors fragmented in the live stage image and “complete” in the constructed projections. The balance between the theatrical and the filmic was key to the collaborative relationship between myself and William Bowden as directors.

Having collectively reduced the novel to a bare-bones sequence of key events, then reorganising these events into a chronology that was best suited to our path through the novel, I would then collate the corresponding passages from the novel into a performance text, which would provide the performers with dialogue but very little else in terms of context. Characteristically of Plath’s prose, this dialogue would often be somewhat fragmented, and would jump between times and locations with little explanation. Feeding in context and explanation was the collective responsibility of the company, who became intimately familiar with the novel and were able to voice individual ideas and interpretations which William and I could then select from in order to build a forty-minute stage version of the book. In our statement of intent we made clear our intention to depart from the source text as much or as little as necessary in order to create a piece that would capture the essence of Plath’s novel but would also allow us to effectively explore what came to be referred to as the aesthetic of chaos.

The way of working that evolved, as described above, eventually led us to a fairly straightforward mode of storytelling. Initially actors worked directly from the novel, but grew frustrated by the sheer amount of information that they were faced with when trying to devise performance book-in-hand. It was at this point that I began to create scripts, based on our collective cut of the novel. In this way, the images and metaphors which received most attention in the rehearsal room were those that the actors instinctively remembered from reading the novel (with the rest fed in by William and myself, who continued to work with the full text in-hand), and therefore I would argue that in this way we were able to instantly tap into the most effective imagery simply by observing what the performers recalled when working with the bare-bones script. This further simplified the editing process.

My day-to-day responsibilities, therefore, were more closely concerned with text and character while William would integrate the “chaotic” elements of live camera and sound construction, adjusting and balancing the composition to accommodate these. Of course it is hugely reductive to suggest that these separate duties defined our overall contribution to the work: there were massive overlaps, not only between William and I but also between the directors and other members of the company. Zakk Hein, for example, heavily influenced the narrative quality of the live camera work through his combined role as performer and projection designer, while my sound design (a role I carried out in conjunction with my role as director) responded enormously to the improvisation work carried out by the performers involved in creating live sound. The set, designed by Charlotte Trotter, evolved through her experience of being “inside” the piece as a performer, and therefore responded more closely to the needs of the cast as a whole. In this way our conscious multi-disciplinary approach led to design work that was fit-for-purpose and thus was key to the congruity of the production.

“In a properly created on-stage world, nothing is extra and nothing is missing.” (Hauser & Reich 59)

Sophie Napleton gave form to Esther’s internal thoughts. Photograph: Will Bowden.

It was observed by a number of audience members that the performance had a cold, clinical quality towards the beginning, gradually warming and becoming more emotionally engaging as the piece progressed. I believe that this is the result of a number of factors, most significantly I feel in the reflection of The Bell Jar’s content and subject matter in the form of the production. The clinical, at times almost sterile tone of Plath’s writing was, as discussed above, one of the primary reasons why we selected The Bell Jar as a source text. By exposing the precise mechanics of theatremaking, we felt able to echo the tone of the prose in the texture of the performance. Though unfamiliar at first, as soon as the spectators warm to the “chaotic” style they begin to realise its creative possibilities.

Speaking of Mitchell’s multimedia work, Aleks Sierz confirms that “video allows her to show the flash of a single thought across an actor’s face” (58): this is but one benefit offered by live construction. The advantages, then, are twofold: first the audience receives an impression of clinical coldness, establishing a suitable atmosphere for the performance; then, as they become more complicit in the image-making, spectators receive a heightened sense of engagement with the storytelling.

This was supported by a secondary device, whereby Esther’s internal thoughts are vocalised by a single performer. Speaking from the symbolic image of a bathtub placed somewhere outside of the main action, Sophie Napleton’s dialogue consisted mainly of the poetic images and metaphors used by Plath to express Esther’s spiralling stream of consciousness. These observations would have been out of place in the main body of the action and dialogue, yet omitting them entirely would have severely compromised the textual tone. Similarly, then, the audience required time to acclimatise to this device, but eventually – as the experiences of the “internal” Esther and the “physical” Esthers began to merge – the device came to function as an emotional anchor.

Incidentally, I would argue that the visual presence of the “internal” Esther within the composition yet fragmented from the “physical” performance is a specific example of the aesthetic of chaos at work without the use of technology; despite this, the decision to use a conspicuous microphone for Sophie’s dialogue was a deliberate attempt to underline her presence as a “chaotic” element.

In our statement of intent we asserted that our confidence in our ability to adapt such a densely layered source text into a clear and effective piece of theatre was primarily rooted in our shared experiences of prior collaboration through previous projects, and the shared vocabulary we have developed as a result. Having completed the work, and made what I am confident can be considered to a reasonable extent as a clear and effective piece of theatre, I thoroughly believe that the success of the project was a result of the collectivity of the company, and the generous contribution that each artist offered. The narrative and aesthetic decisions that we made throughout the process, led by William and myself but shaped by each company member (performers and non-performers), were at all times the result of clear discussion and creative experimentation, generously facilitated by the entire company. The contribution of each individual artist, therefore, was equal and substantial and, in light of the work that we created, the consciously collaborative and multi-disciplinary model of theatremaking is one that we all intend to pursue further.

In particular, we are confident in the effectiveness of intermedial performance as a means of heightening an audience’s engagement with non-linear storytelling. The pleasure that can be found (by both audiences and performers) by being made complicit in the image-making has been key to discovering a process which embraces visual and aural storytelling as a primary means of theatremaking, in equal status to – or even above – a source text. Equally, the aesthetic of chaos, and a multi-disciplinary company, facilitates theatre work that is fit-for-purpose, reflecting in the form the stories and ideas at the heart of the performance.

NB: This essay was written in February 2013. Some minor edits have been made to the original manuscript.

Production details

The production was created by Thrust and developed at Middlesex University between September 2012 and January 2013. It was first performed as part of the Apple Core Festival on 22 January 2013, with the following creative team:

Direction: William Bowden & Bruce Adams

Cast: Zakk Hein, Dan Henry, Ester Mangas Fernandez, Freya Martin, Henry Martin, Tika Mu’tamir, Sophie Napleton, Charlotte Trotter, Harriet Wakefield, Rachel Wood

Set design: Charlotte Trotter

Video design: Zakk Hein

Lighting design: Ryan Funnell

Costume design: Lizzy Gethings

Sound design: Bruce Adams

Stage management: Zoë Sofair & Vicky O’Neill

ASM: Henry Martin

References

Adams, Bruce. ‘The aesthetic and narrative characteristics of chaos within the context of a staged composition.’ Unpublished manuscript. Middlesex University, 2013. Print.

The Culture Show. BBC Two, London, 29 Jul. 2008. Television.

Giesekam, G. Staging The Screen: The use of film and video in theatre; Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. Print.

Hauser, F. and Reich, R. Notes On Directing; New York, Walker & Company, 2003. Print.

Mitchell, K. The Director's Craft; Abingdon, Routledge, 2009. Print.

Mitter, Shomit and Shevtsova, Maria, eds. Fifty Key Theatre Directors; Abingdon, Routledge, 2005. Print.

Plath, S. The Bell Jar; London, Faber and Faber, 1966. Print.

Sierz, A. ‘Some Traces Of Katie Mitchell’ TheatreForum – International Theatre Journal (Winter-Spring 2009): 51-59. Print.