Katie Mitchell and Filter: Staging chaos

In this essay, written while I was an undergraduate in the School of Arts and Education at Middlesex University, I discuss the aesthetic and narrative characteristics of “chaos” within the context of a staged composition, with particular reference to the intersection of live performance and the projected image in Mitchell’s intermedial works at the National Theatre, and the sonic-led work of Filter. It was at this point that I first defined the “aesthetic of chaos”, a principle that has gone on to underpin my later research and practice.

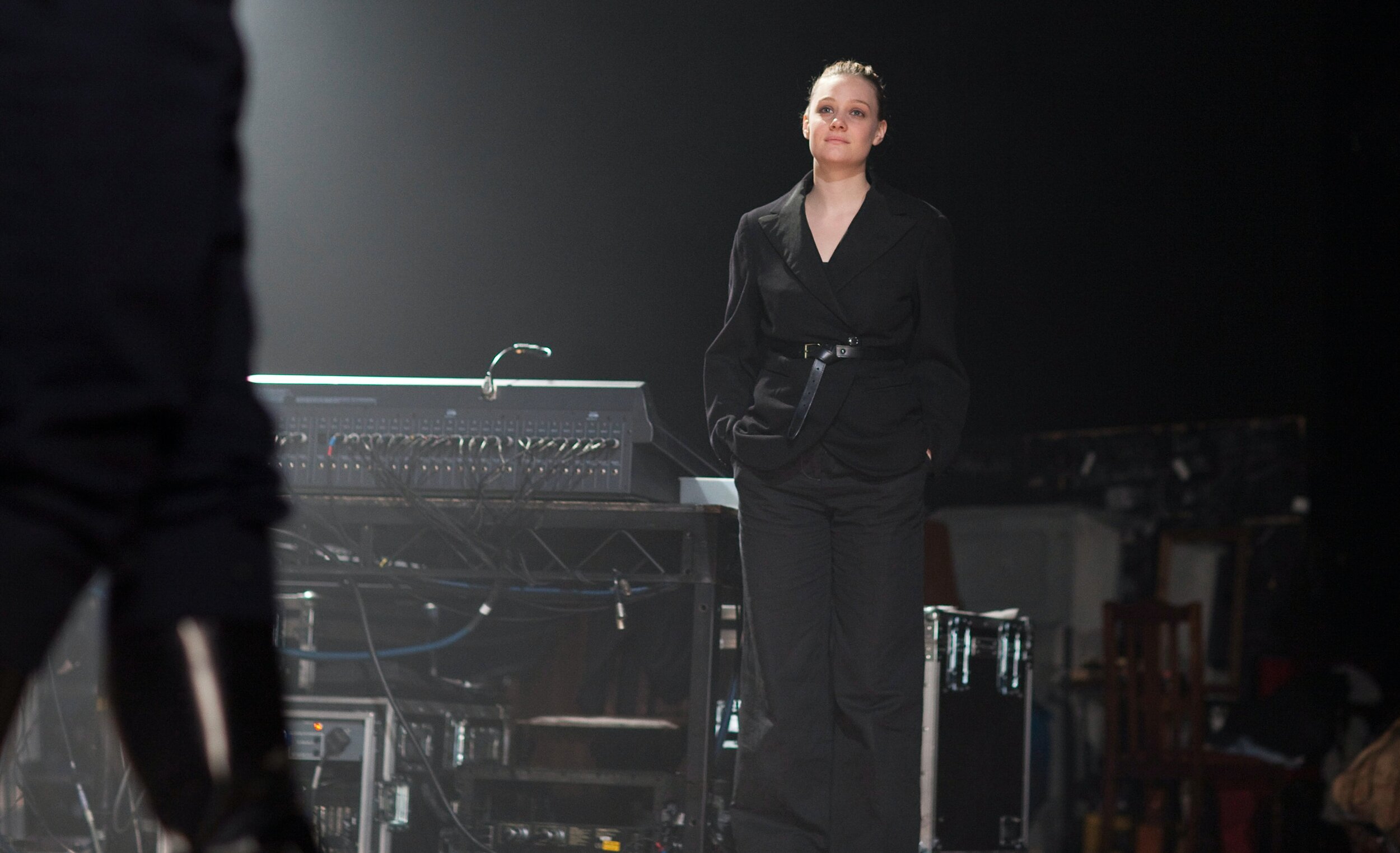

La Maladie de la Mort (dir. Katie Mitchell), 2018. Photograph: Stephen Cummiskey.

“I knew that organising narratives, consecutive scenes and lots of words wasn’t how I experienced myself, relationships or life: everything was slightly more chaotic. And so I was looking for something that resembled that chaos but still had all that feeling in it. And that’s why we started fragmenting the stage picture.”

Katie Mitchell (interviewed by National Theatre)

The word “chaos”, taken in its modern sense as describing a state of complete disorder and confusion, does not seem particularly conducive to theatremaking: an art form which (usually) requires a control-box approach in which a number of elements (performance, lights, sound, scenery, etc.) are meticulously and precisely blended in the presence of a live audience. The word’s roots lie in Greek mythology, where “chaos” referred to the void from which the universe emerged. This sense of something created from nothing, like a piece of performance in a black-box studio perhaps, might be slightly better suited to describing theatre, yet Mitchell’s use of the word – while falling somewhere outside of both definitions – seems more closely related to the former.

Katie Mitchell is not a director known for disorder. Throughout her career she has divided critics and audiences by staging what have been popularly (and arguably erroneously) described as radical interpretations of revered classics, such as the works of Anton Chekhov or Greek tragedies. Accused by some of “arrogantly scrawling her own signature across the stage” (Edwardes), she herself rejects the label of “auteur” that has been pejoratively applied to her, telling several interviewers (including Jane Garvey of Woman’s Hour) that she doesn’t aim for “extreme reactions”; instead she simply intends to make “clear work”. This pursuit of clarity, she argues to Aleks Sierz of theatreVOICE, is inherent in every director’s work, and every director is constantly making subjective, interpretive decisions. Among contemporary theatre directors, Mitchell is perhaps the most acutely aware of this, creating forensic and precise work which explores deep physical and psychological detail.

Faced with the challenge of adapting Virginia Woolf’s 1931 novel The Waves into a work for stage (Waves, National Theatre 2006), Mitchell was compelled to find a solution which combined her psychologically-precise approach with the need to represent a more “chaotic” performance structure, in order to best embody the many possibilities offered by the novel’s stream-of-consciousness form. The solution she arrived at (and expanded on in subsequent productions at the National) was subtle and complex, consisting of many different layers and techniques, but most prominently she used live-feed camera work to construct multiple settings and scenarios.

Essentially, the performance consisted of the actors constructing these scenarios for camera while corresponding passages from the novel were read in voiceover: for instance, as the audience hear:

‘Through the chink in the hedge,’ said Susan, ‘I saw her kiss him.’

…the performer holds a piece of shrubbery to their face and peers through it. On a projection screen above, this is rendered as a realistic close-up of a face seen through a hedgerow (Mitchell 10).

Waves (dir. Katie Mitchell), 2006. Photographs: Stephen Cummiskey.

The juxtaposition of a complete framed image with the visible construction of that image is the essence of the aesthetic of chaos; a term I am proposing and which this essay seeks to explore. While much theatre seeks to conceal the means by which its images are constructed, the chaotic performance consciously reveals it. To take the control-box analogy for theatre, it is as if the “casing” of the box – the proscenium arch, perhaps – has been pulled away to reveal the inner workings and mechanics of the performance. This can apply both tangibly: e.g. to the visual presence of cabling and lighting bars; and intangibly: e.g. to the actor’s “construction” of his own performance.

In ‘Some Traces of Katie Mitchell’, Aleks Sierz describes a typical chaotic set-up:

“The rehearsal room consisted of a dark black box space, with two tables, holding anglepoise lamps and eventually props on either side. In the middle were tracks for a mounted video camera. Also on either side were open shelves for the props and costumes (costume changes were done in full view of the audience). Finally, on either side of the stage, at the front, were the trays used for Foley sound effects.” (54)

It should be noted that, although Sierz writes from inside the rehearsal room of ...some trace of her (2008), the final stage design in the Cottesloe auditorium of the National Theatre did not omit any of these “construction” elements, such as the anglepoise lamps or the props used for foley work. Indeed, in Mitchell’s multimedia works, the disclosure to the audience of these construction methods is the sole function of the stage design (Vicki Mortimer designed both Waves and ...some trace of her); no other decorations or motifs are included.

Filter, a performance company formed in London in 2003, devise new work and reinterpret classic texts. Although their work is not as formally rigid as Mitchell’s multimedia works, their productions share a similar sense of deconstruction and rarely make any attempt to hide the steps taken to compose an image (for argument’s sake, the word “image” may refer to any element of a composition, including “invisible” elements such as sound). Founded on the central tenet that “electronic and live sound-effects should form each scene’s core, rather than lurking on the periphery” (Mountford), much of the chaos inherent in Filter’s performance aesthetic is rooted in their use of live sound.

Three Sisters (dir. Sean Holmes & Filter), 2010. Photographs: Helen Maybanks.

A fitting example can be found in their co-production with the Lyric Hammersmith of Three Sisters (dir. Sean Holmes), during which a tense pause was exaggerated by the sound of a kettle boiling, in real time, while the characters sat in charged silence. The mechanics of this moment were entirely plain to the audience: the stage manager walked onto the stage with a modern electric kettle, placed it on the table, plugged it in, positioned a microphone stand in order to pick up the sound, and set the kettle to boil. Indeed, said stage manager was never absent from the composition at all: in a space stripped of tabs, drapes or flats the bare back and side walls of the theatre were revealed, the wings plainly visible beyond the proscenium, fire extinguishers and electrical fixtures around the periphery of the space, the full height of the fly tower on show with the lighting bars hovering barely a few metres above the stage; the show was called and operated from a control desk separated from the main action by no more than a few feet.

As in Mitchell’s multimedia works, the design (by Jon Bausor) for Three Sisters featured little more than the furniture required to facilitate the performance, which was again included purely functionally without any attempt to “design” for a particular era or mood. However, unlike in Mitchell’s work, a small number of metaphorical touches were included, such as a bunch of helium balloons which became symbolic of the sisters’ hope.

The technical crew became an accepted presence within the performance space. With their function made clear by factors such as clothing (theatre blacks) and equipment (laptops, sound boards, paperwork, etc.), there was no need for the performers or, by extension, the audience, to “pretend” that the crew were not within their world, as tends to be the status quo in naturalistic theatre in those occasional moments (scene changes, for instance) when a member of the stage crew might appear.

And yet, as in Katie Mitchell’s work, the performances themselves (in Three Sisters and also in Filter’s original works such as Water and Silence) consist of naturalistically constructed characters exhibiting perfectly realistic human behaviour. To an extent, one could even argue that the characters also inhabit a naturalistic environment, despite the chaos that frames them. This can be examined via the “hedgerow” example from Waves (above): while it is true that the audience can plainly see (in the “live image”, at least) that there is not a complete hedgerow, if the same moment were to be staged as “conventional” naturalism with a fully-realised “hedgerow” - where would this hedgerow end? (In the wings, presumably.) And would there be soil underfoot and sky overhead? Very probably not. Naturalism, after all, does not require a real hedge, merely the controlled illusion of a real hedge. Under Mitchell’s production aesthetic, the boundaries of this illusion are simply brought in much more tightly, revealing behind it a void – a chaos – filled by the mechanics of that illusion’s construction.

“In high naturalism the lives of the characters have soaked into their environment. Moreover, the environment has soaked into the lives.” (Williams 217)

This does, however, throw up additional questions regarding the distinctions between what is natural for the audience, for the actor, and for the character. Naturalism per se conjures a complete illusion that is shared by all three parties. Within the aesthetic of chaos this experience is fragmented: “the spectators assume the role of editors” (Giesekam 249), and thus, paradoxically, the practice takes on some resemblance to the defamiliarisation effects adopted by Bertolt Brecht in his theatre (Verfremdungseffekt: frequently mistranslated as “alienation”). Meg Mumford, a description of Brecht’s particular interpretation of realism, writes:

“The realist makes it possible to abstract what is significant from the concrete through artistic methods such as selection, isolation and magnification.” (88)

His archetypal “street scene” analogy typifies Brecht’s epic theatre as an act of explanation over reenactment: telling over showing. Through chaotic performance, the audience are told how an image is constructed, but they are also shown the complete (and often realistic) image. In Waves, significant moments are “selected, isolated and magnified” by camera shots carefully constructed in full view of the spectators, while in Three Sisters a metaphorical image (the kettle boiling) is “framed” by constructing it in a manner that is slightly at odds with the naturalistic performance surrounding it.

Specific examples of chaos in Brechtian plays include Deborah Warner’s 2009 production of Mother Courage and her Children at the National Theatre, in which the designers and director “put the emphasis on light, sound, video and the idea that it should look like a gig” (Grylls), and Filter’s earlier production there of The Caucasian Chalk Circle (2007), which similarly included their familiar aesthetic of on-stage mixing desk and musical instruments. Here the effect is used to Brecht’s intention; Lyn Gardner described the production as “a playful spin on the dry concepts of alienation and the epic … you have to keep retuning your radio”; and yet in the same company’s later devised work, Water (2011), the very same chaotic staging aesthetic achieves the opposite of Verfremdungseffekt:

“[The cast] slips between roles, as well as supplying sound effects or holding props when required ... The let’s-pretend staging helps the show’s pace and illuminates its theme. Human contact is mediated by technology throughout. The point underlies everything we see but isn’t allowed to underline it … the characters acting as if they are all separate are portrayed by a cast we see mucking in together throughout, [which is something] that could only be done live on stage. [It is] adventurous, accessible [and] affecting too.” (Maxwell 16)

Mother Courage and her Children (dir. Deborah Warner), 2009. Photograph: Anthony Luvera.

Here Dominic Maxwell confirms the chaotic staging as a significant contributor to the emotional and perhaps empathetic impact of the piece, dangerously at odds with Brechtian defamiliarisation: “sympathy is acceptable in Brecht’s theatre but not empathy” (Eddershaw 16). And yet “let’s-pretend staging” hints at a resemblance to Warner’s Mother Courage, in which settings were represented by white screens bearing written labels, such as one reading “A FARMHOUSE” underneath another reading “A THATCHED ROOF” (both rectangular and completely unshaped or coloured or otherwise designed). Designer Tom Pye described this as “pure Brecht”, “taking what he had suggested and pushing it to its most extreme” (Grylls).

This, of course, is the absolute opposite of naturalism, and yet the “let’s pretend” environments created in Water supported much more realistic performances with equal ease. Thus the aesthetic of chaos is demonstrably able to facilitate both Brechtian and Stanislavskian performance modes and, to an extent, Brecht’s ideas are used against him. Indeed, Margaret Eddershaw rejects the “binary opposition” (8) between Brechtian and Stanislavskian (ie, naturalistic) practice, and the aesthetic of chaos demonstrates a path between the two.

Mitchell continued her experiments at the National Theatre with ...some trace of her, “a revolutionary work that not only expresses the psychological naturalism of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The Idiot (1869) but also reveals the aesthetic and theoretical potential of intermediating artistic forms in the current landscape of electronic technologies” (Hadjioannou & Rodosthenous 44). Again, the use of meticulously constructed live camera shots and foley work (the latter very much in common with Filter) provided the visual and narrative core of the work. Speaking to the The Culture Show about the audience’s relationship with the performance, Mitchell highlights the way in which the production aesthetic reinforces to the audience that the entire piece is “completely live”, coupled with the inherent danger that it could at any moment “go wrong”; arguing that this danger and liveness is central to their engagement with the production: “there’s a great delight in participating in that”.

This precariousness is inherent in both the live performance work and the artificial elements such as lights, sound and, of course, live feed. Watching actors take on multiple roles, even fragments of roles (in ...some trace of her a performer might put on the bottom half of a sleeve, from elbow to wrist, in order to “play” a character’s lower arm in close-up), with all costume changes seen live on stage (often while simultaneously preparing the next shot), reinforces to the audience the degree of craft and complexity invested in the production by the performers. In particular, where performer and technology meet, “the demands on the actors are enormous” (Sierz 56). Throughout the course of the evening the individual performer must complete an extensive and intricate series of tasks which involve anything from speaking a line, to focusing a camera, to creating a sound effect. As “each actor’s journey through the evening was uniquely different” (Grylls “Re-inventing”), in place of a script each actor compiled a personal “manual” listing these tasks as the work was developed:

Through this undisguised interaction between performer and hardware, the visible presence of technology therefore plays an integral role in the aesthetic of a chaotic performance, acting as “a live participant, with almost equal status to an actor” (Mitchell “Craft” 90). The exposed mechanics of the performance reveal the act of theatre as a machine, within which actors and apparatus are balanced components.

But it also serves a narrative function. To stage The Waves, for instance, as a conventionally text-based piece of naturalism would do the novel a disservice; thus Mitchell’s foray into experimentation with multimedia was not an aesthetic agenda imposed on a text she happened to be working on but a considered response to the narrative requirements of the source text.

“Film’s ‘liberations’ from the space-time continuum firmly aligned silent-era film-making with the modernist play, with stream of consciousness in the novel, or with the collapsing of perspectival space in fine art.” (Keil 80)

The broken soliloquies which make up Woolf’s novel necessitated the development of a form that would support this fragmented experience of life, which indeed Mitchell (in the title quote) asserts as closer to true human experience in any case. The fragmented, chaotic aesthetic is a “reminder that whatever we see, not only in theatre but in the wider media, is a construction” (Sierz 58), and thus has a strong narrative resonance.

However, an important distinction lies between Katie Mitchell’s practice and that of Filter. While Filter consistently apply a chaotic aesthetic to their productions, Mitchell has not worked in the multimedia format since 2008* (with the exception of Ten Billion for the Royal Court and Festival D’Avignon in 2012, which took the form of a “theatrical lecture” using an interactive projection design). Thus, the aesthetic of chaos has been absent from her recent work. This may, in part, relate to her choice of source texts in recent years, which have mostly consisted of scripted dramas staged in her characteristic style of psychological realism. One notable exception has been small hours (Hampstead Theatre, 2011) which, although “written” by Lucy Kirkwood and Ed Hime**, resembled much more closely a company-devised work (though a solo performance) in the vein of Waves or ...some trace of her. Like those works at the National Theatre, the piece explored internal human experience (in this case, post-natal depression) and yet its design - a fully-realised London flat with enclosed floor, ceiling and walls, lit by domestic lamps and fixtures and with audience seated on the furniture - bore no “chaotic” elements.

One must therefore assume that Mitchell took a narrative decision that the chaotic aesthetic of her previous devised works would not be appropriate for small hours. The overwhelming experience of small hours was the feeling of being completely lost in the protagonist’s experience: the audience are “pulled into this immersive world, to the point [at which they] lose track of time with her” (“Review: small hours”). In her multimedia works, however, although the productions are intentionally crafted to achieve emotional resonance – “Mitchell’s company added [layers] of subjectivity” (Sierz 53) – they also aim to objectively assert the theatrical craft which, through its liveness and risk-taking, speaks to and frames human experience, but also creates an additional layer between the story and the audience.

To put it another way: small hours draws one directly into the experience of another, while Waves or ...some trace of her seek to frame one’s own experience of life by exposing the construction of another’s thoughts.

Filter, perhaps more restricted by the need to create work which is consistent with their reputation as a company than Mitchell is as an individual, continue to apply the aesthetic of chaos to all of their productions. However, the degree to which the technique is employed varies. Construction of the stage images is revealed with little hindrance in all of their devised works, as well as in revivals such as Three Sisters, however in their 2012 interpretation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Lyric Hammersmith) the mechanics of the staging are revealed more slowly and with more reservation. Perhaps the contrast between their use of these two classic texts lies in their relationship with the audience: Three Sisters speaks of the universal human experiences of hope and loss, while A Midsummer Night’s Dream exists much more for the sheer delight of storytelling. The aesthetic of chaos, then, seems much more effective towards the former end of the spectrum.

“Where a production does not attempt to disguise its mechanics and the performers adopt a presentational style which acknowledges the fact of performing and the presence of the audience, they establish a complicitous relationship in which the audience shares the challenges they face in working with the mediated imagery. Unlike the naturalistic actor who tries to disguise the work of performance, performers here lay bare the making of the performance. Such work implicitly acknowledges the spectators’ role in completing the performance – something which applies to all theatre, of course, but which is often ignored.” (Giesekam 249)

Through their varying applications of the aesthetic of chaos, both Katie Mitchell and Filter allude to a more honest theatrical experience, taking an “aesthetic stand” (Sierz 51) against the conventional practice of disguising the construction of these naturalistic images and, as Filter seem to allude to in their choice of company name, leave in what other theatre-makers would filter out. The result is a fragmented, but often truer, slice of life.

NB: This essay was written in February 2013. Some minor edits have been made to the original manuscript.

Footnotes

* Since this essay was written, Mitchell has returned to and refined the Live Cinema genre numerous times.

** The piece contained almost no spoken word, the only speech being a “conversation” with an automated cinema booking system and the leaving of a voicemail message.

References

‘Chaos.’ Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 1989. Web. 6 Feb. 2013.

The Culture Show. BBC Two, London, 29 Jul. 2008. Television.

‘Director Katie Mitchell defends her work’ Narr. Aleks Sierz. theatreVOICE. V&A Department of Theatre & Performance, 12 Aug. 2008. Web. 10 Feb. 2013.

Eddershaw, M. Performing Brecht: Forty years of British performances; London, Routledge, 1996. Print.

Edwardes, Jane. ‘Katie Mitchell: interview’ Time Out London. TimeOut, n.d. Web. 10 Feb. 2013.

Gardner, Lyn. ‘The Caucasian Chalk Circle review’ The Guardian. Guardian, 12 Mar. 2007. Web. 11 Feb. 2013.

Giesekam, G. Staging The Screen: The use of film and video in theatre; Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. Print.

Grylls, Pinny. ‘Creating a visual narrative’ NT Discover More. National Theatre, 2009. Web. 11 Feb. 2013.

Grylls, Pinny. ‘Re-inventing the script on a multimedia production’ NT Discover More. National Theatre, 2009. Web. 12 Feb. 2013.

Hadjioannou, M. and Rodosthenous, G. ‘In between stage and screen: The intermediate in Katie Mitchell's ...some trace of her’ International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 7:1 (2011): 43-59. Print.

Innes, C. ed. A Sourcebook On Naturalist Theatre; London, Routledge, 2000. Print.

Keil, C. ‘All The Frame's A Stage: (Anti-)Theatricality and Cinematic Modernism’ Against Theatre: Creative Destructions on the Modernist Stages ed. Alan Ackerman and Martin Puchner. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. Print.

Lane, D. Contemporary British Drama; Edinburgh, E.U.P., 2010. Print.

Maxwell, Dominic. ‘The show with the flow: Filter subtly blend storytelling and stagecraft’ The Times (London) 8 Feb. 2011. Print.

Mitchell, K. The Director's Craft; Abingdon, Routledge, 2009. Print.

Mitchell, K. Waves; London, Oberon Books, 2006. Print.

Mitchell, Katie. Interview by Jane Garvey. Woman's Hour. BBC Radio 4, London, 30 Nov. 2007. Radio.

Mountford, Fiona. ‘Faster review’ Evening Standard (London) 8 Apr. 2003. Print.

Mumford, M. Bertolt Brecht; Abingdon, Routledge, 2009. Print.

Sierz, A. ‘Some Traces Of Katie Mitchell’ TheatreForum - International Theatre Journal (Winter-Spring 2009): 51-59. Print.

‘Review: small hours, Hampstead Downstairs’ There Ought To Be Clowns. Blogspot.co.uk, 18 Jan. 2011. Web. 12 Feb. 2013.

Whitmore, J. Directing Postmodern Theater: Shaping signification in performance; Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1994. Print.

Williams, R. ‘Social Environment and Theatrical Environment: The case of English Naturalism’ English Drama: Forms and Development ed. Marie Axton and Raymond Williams. Cambridge, C.U.P., 1977. Print.